Human nature begs for community. We crave connections—friends to claim as ours, groups to which we belong. Our reasons could run like a ticker tape:

- Shared glory

- New access

- Social acclaim

- Financial benefit

And perhaps the most simplistic reason—we hate to feel alone.

Strategic connections aside, we hang tenets of our identities on our connections. I’m a dad to my children, a child to my parents. Stripped of our connections, we too commonly feel adrift in some sea of indeterminateness.

We loathe the feeling of abject ambiguity.

So we conform to some larger group—wear the social uniform expected of our chosen peers, consume the standard nutritional and educational diets of our culture, embrace the commonplace opinions on social matters otherwise inconsequential insomuch as they mark our selected group as distinct.

In other words—we go along to get along.

The Asch paradigm (commonly cited in psychology classrooms) exemplifies this pattern. In the 1950s, Solomon Asch conducted “conformity experiments” to determine if people measurably agree with a group to avoid rejection or ridicule.

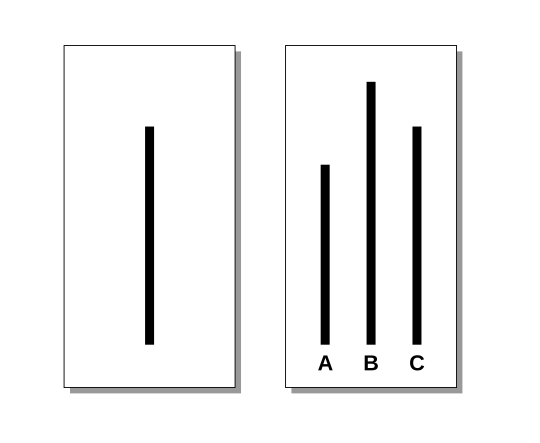

Imagine: you’re placed in a room with seven other participants. You’re shown two images, one of a single line, and one of three lines of varying length.

The researcher asks you to identify which line on the second image is the same length as the line on the first image. To you, dear reader, it likely seems obvious that Line C is the correct answer.

But imagine if the first participant asked responds that Line A is the same length. Participant Two also says Line A. As Participant Three responds in kind, the disbelief slaps you across the face. Surely your eyes still function. Perhaps, you wonder, it’s an optical illusion?

As every participant, one after the other, selects Line A, the researcher then turns to you. Against your own judgment, you agree with the group—Line A is the same length as the first image.

Here’s the catch—the other participants were actors, directed to respond with an incorrect answer. You just went along with the majority to avoid feeling left out of the group.

The study (originally, and in replications for the past 70 years) found that over 99% of participants correctly identified Line C as the matching line when asked to give their answer alone or in writing. People weren’t genuinely getting the answer wrong. When actors gave the correct answer, participants had no issue selecting Line C. Even as actors first, in subsequent questionings, began to selected Line A, participants often continued to choose Line C. With repeated opportunities, however, the burden of standing alone grew too heavy.

In a series of 12 rounds of questioning in which the actors chose the incorrect answer, over 75% of participants eventually gave in and agreed with the group. Human nature deplores isolation, and emotions accumulate. While it feels reasonable—even necessary—to call it how you see it, it seems most people will go along to get along.

We’d rather share a lie than stomach the truth alone.

Ironically, embracing what we believe untrue—if just to “fit in” with a crowd—leaves us feeling rather more isolated than before. It’s as if we intuitively understand rejecting our beliefs to gain acceptance does little to change our beliefs. We put on a mask so we don’t get ridiculed by the masses.

But with our faces hidden, we miss opportunities to find other people willing to identify Line C as the correct answer. When researchers tweaked the experiment and instructed one actor to give the correct response, 95% of participants would choose Line C—no longer the isolated contrarian. Just one consenting voice provided enough confidence to reject the majority.

When embraced in community, the truth seems worth defending. We want to stand up for what we believe. We just care more about acceptance—we want to fit in, to be liked, to belong.

We’d rather hold half-truths and misinformation together than bear the weight of truth alone. It’s what makes deception contagious and enables it to spread like wildfires. Strategically unleashed chaos cares little about the destruction it promises.

So as you see news, read articles, or hear conversations and Line A clearly doesn’t match the accurate standard, pick Line C. When you go along to get along, the next person in line will almost certainly do the same.

Yet it’s possible to share truth—to carry honest answers in community. For every person bold enough to stand in line and answer “Line C” when everyone else turns a blind eye to the truth, someone else in line gleans the confidence to call it like it is.